Feature Image: Albumen photograph by Frank Hartwell of the Adams Hotel (Phoenix, Arizona Territory) soon after completion ca 1898. The fire occurred on May 17, 1910. This image was reproduced on printed postcards. Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography – Vintagephoto.com.

Fire was a common tragedy in the growing cities of the Southwest. Phoenix, Arizona had several major fires during its Territorial era:

September 2, 1871 – Less than a year after its founding, Phoenix saw its first major enterprise, the Bichard Flour Mill at the corner of Center and Jefferson Streets completely destroyed by fire.

August 28, 1885 – About 2:00 a.m., fire swept down the north side of Washington Street between Montezuma and Second Streets leaving adobe façades, but destroying the wooden structures behind. After the fire, the damaged adobe was recycled and used to grade the streets as the town rebuilt.

August 6, 1886 – About 3:30 a.m., fire broke out in the newly rebuilt business district and this time destroying the area along Washington Street between Center and First Streets.

In the hot August weather of Arizona, there was no need of a wood stove for heat, so given the time the fires started, an overturned kerosene lamp might be likely suspects for these fires.

As Phoenix grew several hotels were built. The Adams Hotel being the finest. Built at a cost of $200,000 in 1886, the four-story brick and wooden building was the tallest in the city. It had about 8,000 square feet per floor and offered meeting areas for the Commercial Club, a civic organization to promote social, economic and philanthropic programs. It could accommodate over 200 visitors in its guest rooms – “two-thirds” with private toilets. The hotel had 11- to 13-foot-wide wraparound verandas on each floor, and a tall octagonal belvedere topped with a flagpole, as its signature design elements. The Adams was the premier hotel in the region, and after Phoenix became the capital of the Territory in 1889, housed scores of businessmen and notables visiting the rapidly growing city.

The fire in the basement of the Adams Hotel started early in the morning of May 17, 1910, likely in a storage area for the hotel pharmacy. The fire quickly spread up the elevator shaft into the lobby, then down the corridors and up into the rest of the building. Like the previous blazes, the cause was never identified.

Though Phoenix had grown, it had not invested in the infrastructure and human resources needed to fight a large, multi-story fire in a large wooden building like the Adams. Phoenix still used a volunteer fire department.

The volunteer firefighters had access to a double action pumper with two groups of men providing power and water pressure by pumping from either side. It was named the “Yarnell Pump” for its private owner, Harry Yarnell. Harry used the pump to water down the dirt streets and had a maximum range of about 50 feet with men furiously pumping on both sides. The pumper was typically stored on South First Street within a few blocks of the hotel. The water supply needed to fight fires still came primarily from private wells when fighting residential fires, but more frequently from the ditches adjacent to the streets which often could not provide sufficient water. Volunteer firefighters often had to rely on a “bucket brigade” to get water to fight fires.

The morning of May 17, volunteer firefighters quickly arrived at the burning hotel, as did scores of locals drawn by the pistols fired to alert the public to join the arriving firefighters as smoke billowed from the burning building. The fire quickly raged out of control, and the firemen strained to try to prevent the fire from spreading beyond the hotel to adjacent buildings and across the streets to other blocks.

Among the guests staying at the hotel when the fire broke out was Arizona Gov. Richard Elihu Sloan and his family. Sloan had stayed up to watch Halley’s comet the night before and was asleep in his room while his wife and daughter slept on the portico. In the confusion caused by the smoke, the night clerk, Henry Willey, ran to the governor’s room and carried his daughter, Marion, to safety. The governor and his wife escaped over the balcony railing and onto the awning above the sidewalk then jumped into an express wagon brought to help guests escape from the hotel. Initially it was thought that everyone had safely evacuated from the building, but the investigation later confirmed that two individuals died in the fire.

Several local photographers made real photographic postcards that documented the event. Some of the images appeared in the local newspaper and were also produced as printed postcards. Robert Turnbull was probably the most entrepreneurial, offering several images of the loss of the historic hotel.

The owners quickly rebuilt at the same location. The new five-story building was made of poured concrete and was noted as being “Absolutely Fireproof.” The Adams Hotel remained an important Phoenix landmark with the new building lasting until 1973 when it was imploded for a new larger hotel.

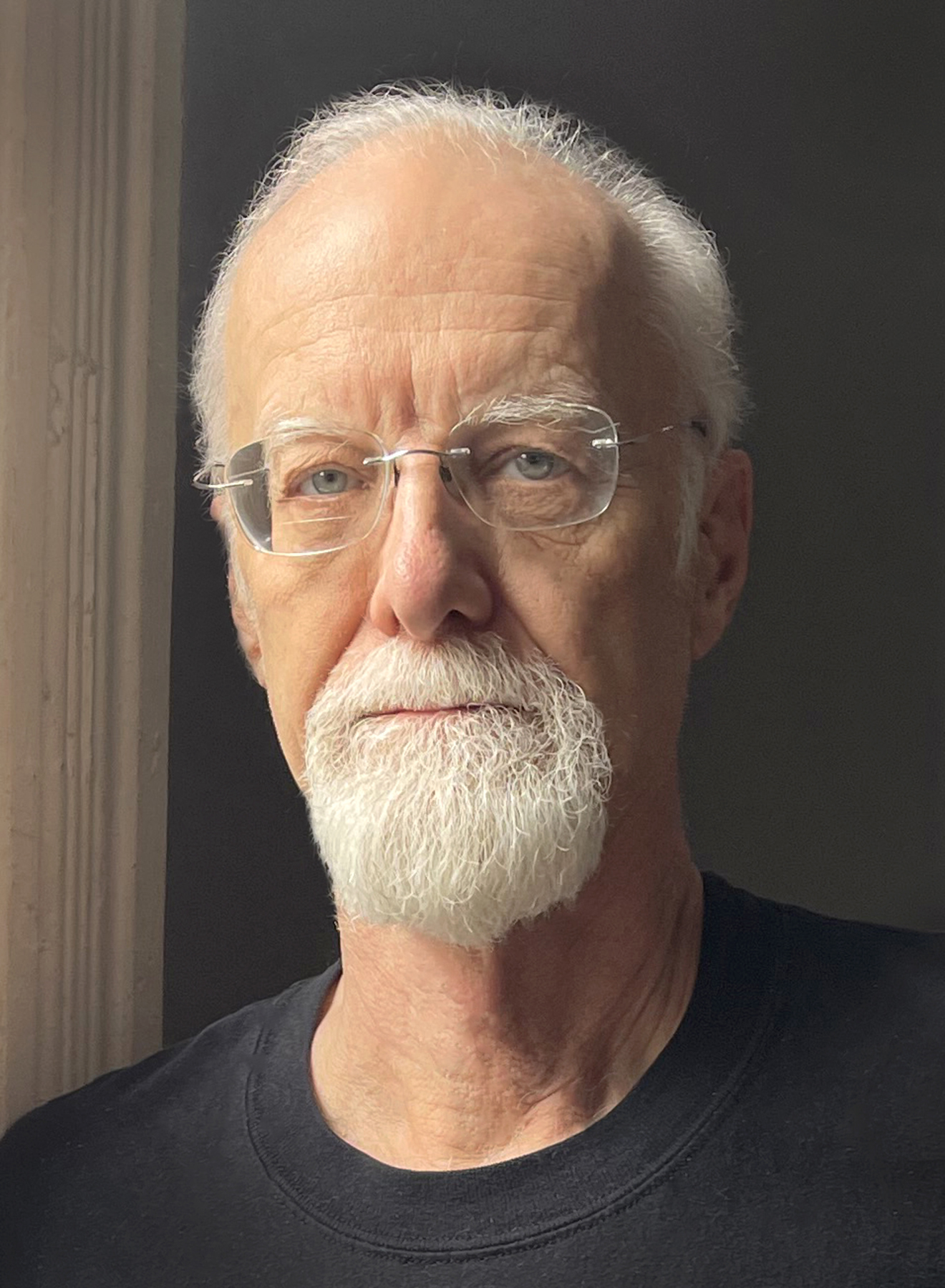

Jeremy Rowe

Contributing Writer

Jeremy Rowe has collected researched and written about historic photography for over 30 years. His collecting has focused on 19th and early 20th century photographs – ranging from daguerreotypes and cased images to mounted photographs, real photo postcards, and vernacular images with an emphasis on Arizona and the Southwest, Lower Manhattan, and the open-ended category of “images that strike me.”

Jeremy has curated exhibitions and served on the boards of the Daguerreian Society, National Stereoscopic Association, Daniel Nagrin Film, Theater and Dance Foundation, In Focus, and Ephemera Society of America. Jeremy is currently working with the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs to establish a National Stereoscopic Research Collection and Research Fellowship.

Jeremy has written numerous publications about historic photography, including Arizona Photographers 1865 – 1920 a History and Directory, Arizona Real Photo Postcards a History and Portfolio, and Arizona Stereographs 1865- 1930.

Jeremy has three degrees from Arizona State University and is an Emeritus Professor. He is currently a Senior Research Scientist at New York University and travels between New York City and Arizona.