Feature Image: 4” X 5” Autochrome of two young girls in costume dancing. Photographer unknown, 1920. Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography – vintagephoto.com

From its invention, photography sought ways to capture color. Initially photographers added color by hand. Periodically inventors and entrepreneurs like Levi Hill claimed to have devised systems to capture full-color images.

Before practical processes were available, early pioneers like James Clerk Maxwell and Thomas Sutton laid the theoretical groundwork for color photography. Maxwell’s tri-color theory proposed that any color could be created by combining red, green and blue light. Sutton’s experiments with three-color separation photography provided a conceptual framework for future innovations in techniques and cameras to use monochrome emulsions to capture the three colors.

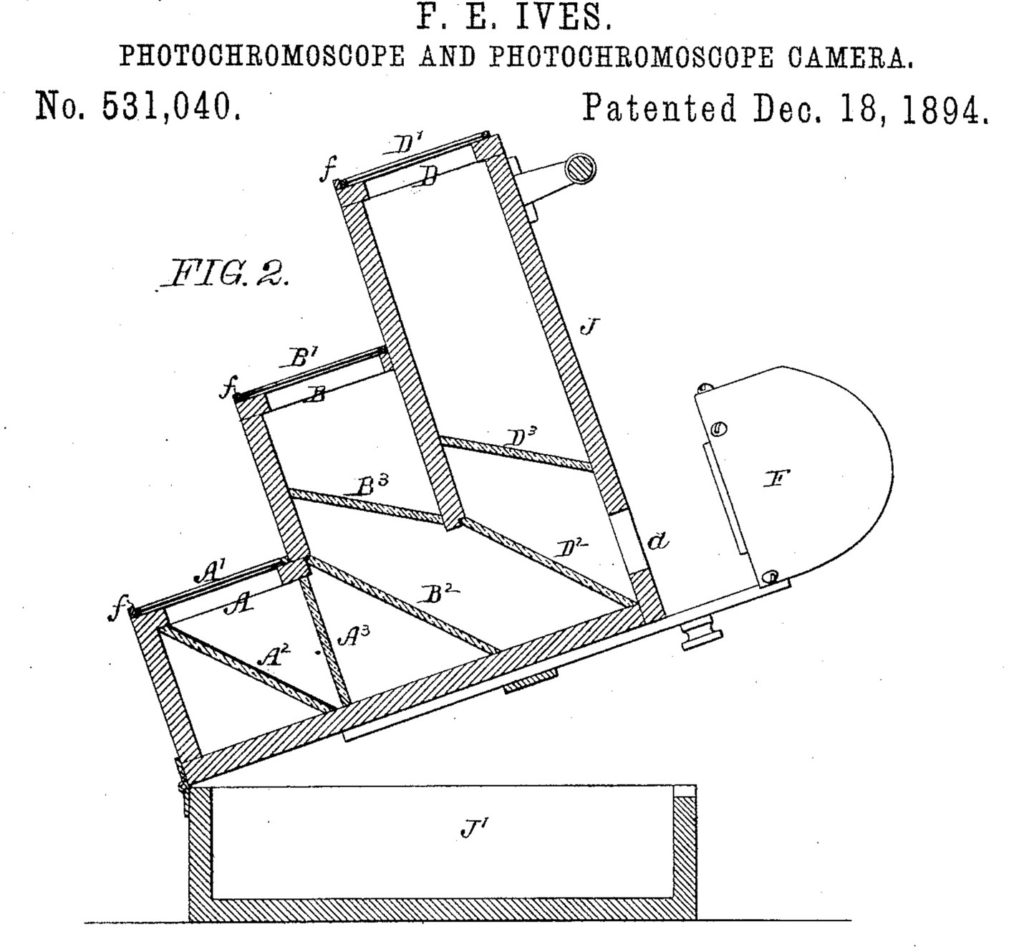

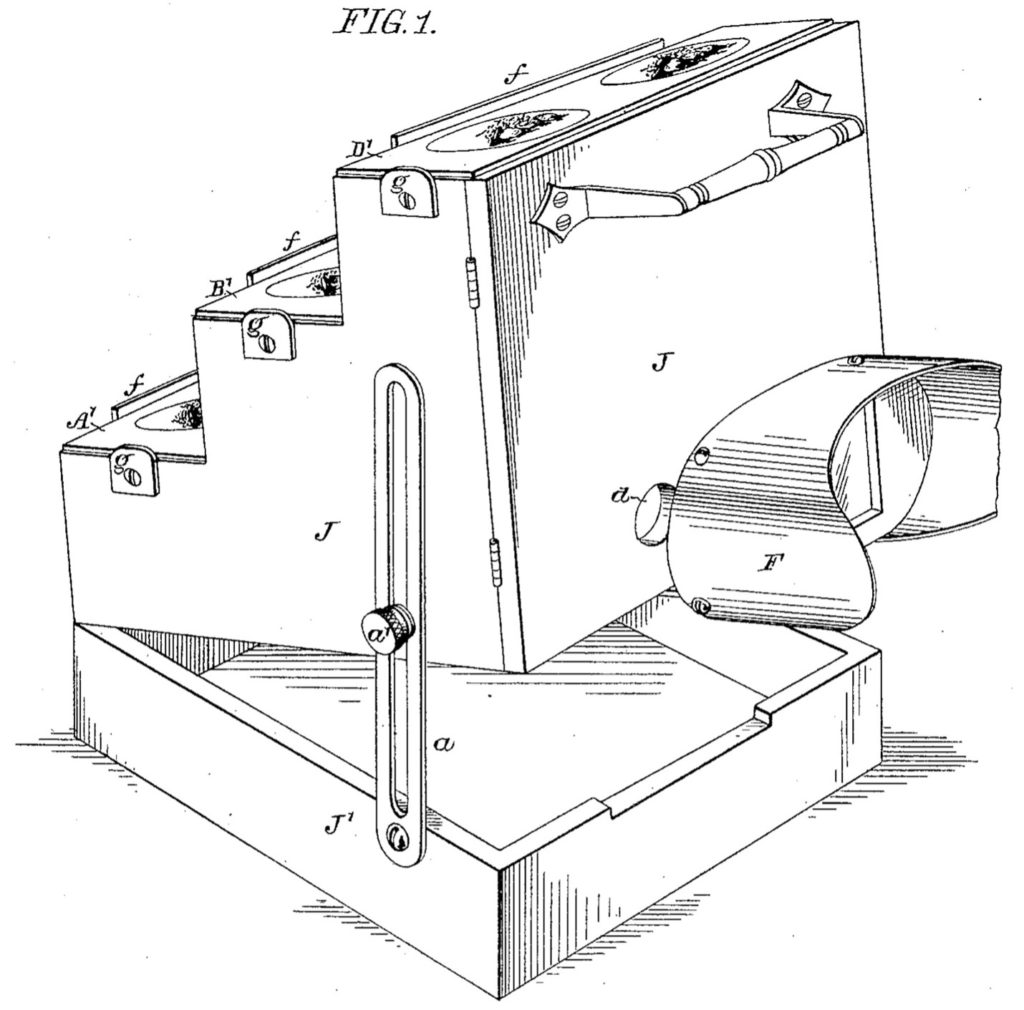

Frederick Eugene Ives had developed early halftone reproduction processes in the late 1870s and introduced his Heliochromoscope to capture full-color images in 1892. Ives built upon Maxwell’s color theory with his three plate, three-color process, also known as the Kromoscope.

Patent drawing of Ives Kromoscope design showing placement of the three images (A, B and D) that were combined using internal mirrors to provide a full color image when viewed.

Patent drawing exterior view of Ives Kromoscope design showing placement of the three images (A, B and D) that were combined using internal mirrors to provide a full color image when viewed.

Ives used red, blue and green colored filters and three photographic plates to capture the color information. The sets of the three images were called Kromograms, and Ives offered monocular and stereoscopic viewers, and a triple lantern slide projector that could combine the three images with color filters to view or present full-color images. Ives sold his own Kromogram images, viewers and projectors as well as special cameras and attachments for those wishing to make their own color images.

Detail of 4” X 5” Autochrome of two young girls in costume dancing showing the pattern of the potato starch layer. Photographer unknown, ca 1920. Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography – vintagephoto.com

Auguste and Louis Lumière introduced a single-plate color process, the Autochrome Lumière plate in 1907. The Autochrome process used a layer of microscopic grains of potato starch dyed in red, green and blue over the emulsion. These grains acted as color filters, allowing the plate to capture a full-color image in a single exposure. Autochrome Lumière plates were commercially available, and despite the long exposures required by the layers of filters, became popular. Like Ives Kromoscope images, Autochromes were commercially produced but amateurs could buy prepared Autochrome plates to make their own images.

A year later, Charles G. Matthews and David A. Klein introduced the Paget Color Process, which like the Kromoscope used three separate plates to capture the red, blue and green color information to permit production of a full-color image.

Another competing single exposure process, Dufaycolor was introduced in 1931. This process used a color screen composed of lines of red, blue and green filters to create color separations that were needed to produce a color image.

Though the red, blue and green images needed to reproduce color for printing could be made of still images by three successive exposures through the appropriate filters, several manufacturers produced cameras that could make the three separate red, blue and green images simultaneously through a single lens.

These cameras used prisms or beam splitting mirrors to expose three plates, each through the appropriate filters to compensate for the difference in color sensitivity of the photographic emulsions. The process significantly reduced the amount of light for each plate and required fast lenses and additional exposure, but was more convenient than making three separate exposures.

Bermpohl 9 X 12 cm. Naturfarbenkamera (natural color camera ca. 1930 front view). Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography – vintagephoto.com

An example is the Naturfarbenkamera or natural color camera produced by the Bermpohl company in Berlin beginning about 1930. Bermpohl previously made traditional, single-lens cameras that could be used for three-color photography by successive (i.e., not simultaneous) exposure of the three plates. The need to make three different exposures worked for still subjects but was cumbersome. Any jarring or movement of the camera or subject between exposures required starting over.

The Naturfarbenkamera had a single lens and used internal beam splitting mirrors to simultaneously expose three sheets of black-and-white film to make color separation images in a single exposure. The camera was designed to accommodate a color filter and film holder with dark slide for each of the required red, blue and green exposures.

The Bermpohl Naturfarbenkamera cameras were sold with a Meyer f/4 Doppel Plasmat lens in a dial set compound shutter and were available in three plate sizes (9×12 cm, 13×18 cm, or 18×24 cm).

Bermpohl 9 X 12 cm Naturfarbenkamera (natural color camera top view) showing the design of the camera needed to position the red, blue, and green color images separated by the internal mirrors and locations of the ground glass, filters and film holder for each color. Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography – vintagephoto.com

Bermpohl Naturfarbenkamera or natural color camera film holders and red and blue color separation glass filters. Because contemporary monochrome film was more sensitive to blue than to red, the strength of the color filters was biased to compensate. Collection of Jeremy Rowe Vintage Photography – vintagephoto.com

Several other manufacturers made similar tri-color cameras. Within a few years, color film like Kodachrome became commercially viable, and the market for color photography exploded. Tri-color cameras like this Bermpohl Naturfarbenkamera fell out of favor and were soon relegated to studio storage rooms and eventually museums and collectors.

Jeremy Rowe

Contributing Writer