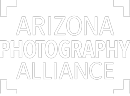

Feature Image: 2 ¼” X 3 ¼” Curtis Color-Scout aluminum bodied single shot, tri-color, color separation camera in horizontal position showing auxiliary sport viewfinder. Note the three black guides that mark the slots for the film holders with the integrated red, green and blue colored filters needed to make the B & W color separation negatives.

The Curtis Color-Scout was an aluminum bodied 2 ¼” X 3 ¼” camera designed to produce negatives that could be used to produce color prints using the Chromatone process.

The camera used two internal mirrors and three film holders with integrated red, blue, and green color filters to produce the three B & W color separation negatives with a single exposure. The camera was produced to compete with offerings by other manufacturers like the European Bermpohl Naturfarbenkamera in the amateur and semi-professional tricolor camera market that emerged in the early 1930s but was rapidly supplanted by the late 1930s with the emergence of Kodak Kodachrome color film and paper processes which rapidly became the industry standard.

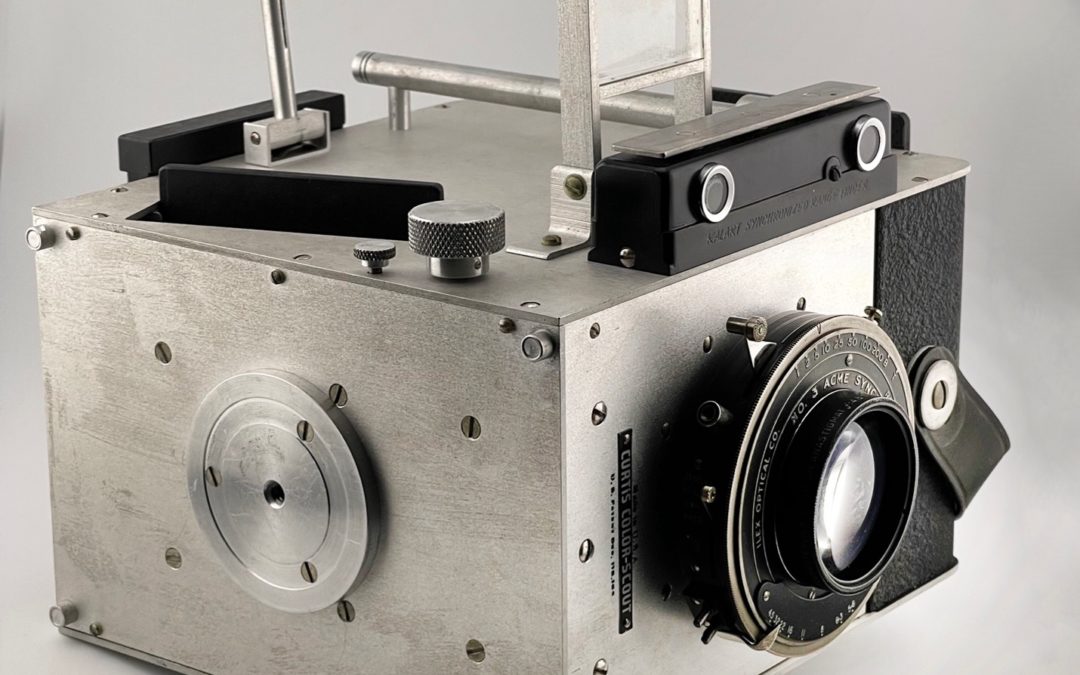

The Curtis Color-Scout was manufactured in Huntington Beach, California, and was introduced in 1941, just before WWII by the Thomas S. Curtis Laboratories. It was an expensive camera, priced at $232 for a bare body, and $280 with a Tessar lens in a Compur shutter (about the same as a CONTAX III with an F/2 Sonnar lens – equivalent to a little over $6,000 today).

The marketing “hook” for the Curtis was the claim of faster exposure speeds compared with other tri-color cameras due to the Curtis Diafon mirror design. Curtis also offered a guide to using the Chromatone process to make color prints.

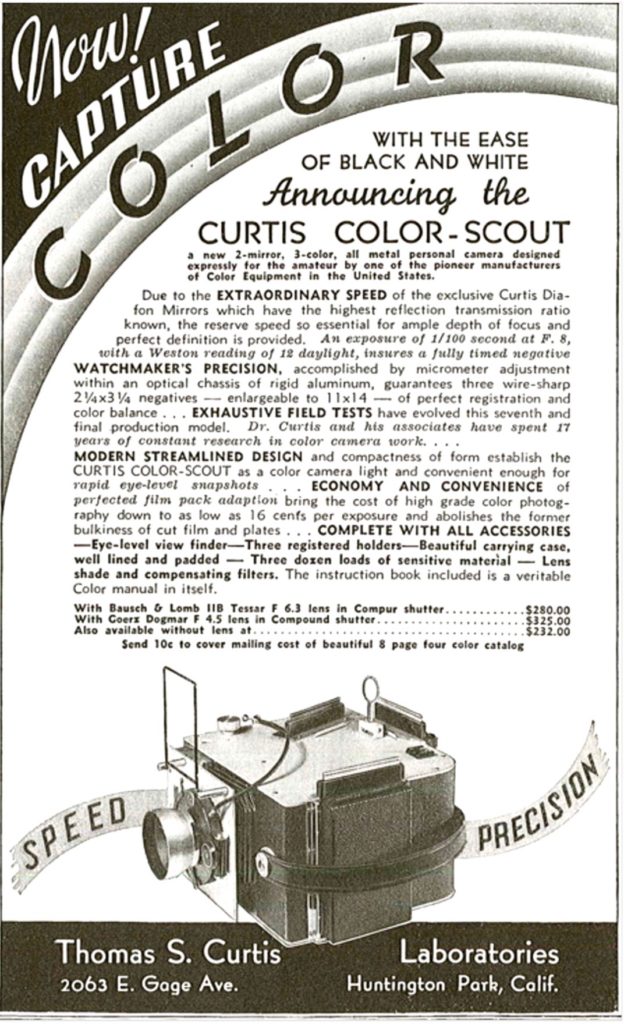

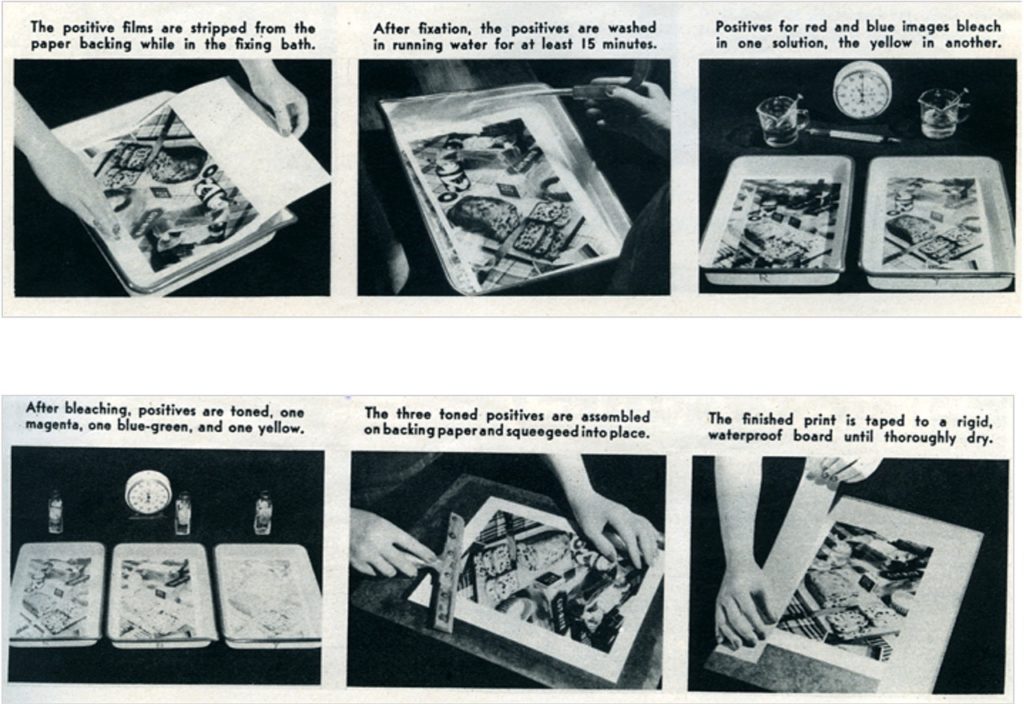

Two chemists, Francis Snyder and Henry Rimbach, developed the process in 1935 to make images to support their microphotographic research. The Chromatone process used a special collodion film that permitted the thin emulsion layer to be stripped from the backing paper. Each of the B & W color separation negatives were printed, fixed, and washed. In white light, the emulsion was stripped from the paper backing and bleached. Each of the three collodion positive images that were produced were then toned using the appropriate color Chromatone toner. The print from the red image was toned with the blue/green (cyan) toner, the green image print with magenta toner and the blue image with yellow toner.

After toning, the three collodion layers were assembled one-by-one on a clean white sheet of paper coated with gelatin and squeegeed in place. One can only imagine the difficulty in aligning and correctly registering the three delicate layers of collodion over each other without damage. The description of the process makes it easy to see why Kodachrome and other full color processes quickly replaced complex processes like the Chromatone.

Between the replacement of the intricate hand-made processes with new color film and printing papers, and the dramatic economic shifts at the beginning of WWII, the single shot tri-color cameras never sold well. We may never know how many examples of cameras like the Curtis Color-Scout were originally produced, but today they are rare and collectors’ items with an interesting story that represents an evolutionary branch of photographic equipment quickly made obsolete by technical innovations in color film and paper processes.

Advertisement for the Curtis Color-Scout single shot, tri-color camera. The $280 purchase price for the version with f6/3 Tessar lens in a Compur shutter in 1941 is equivalent to a little over $6,000 today.

Diagram of the steps in the Curtis Chromatone color printing process. Note that red, green and blue filters were used to produce the B & W negatives, and blue/green (cyan), magenta, and yellow dyes were used to produce the collodion layers that were assembled to create to the final print.

The 2 ¼” X 3 ¼” Curtis Color-Scout aluminum bodied single shot, tri-color, color separation camera in vertical position.

Original set of 2 ¼” X 3 ¼” Curtis Color-Scout Film holder with integrated red, green and blue color filters.

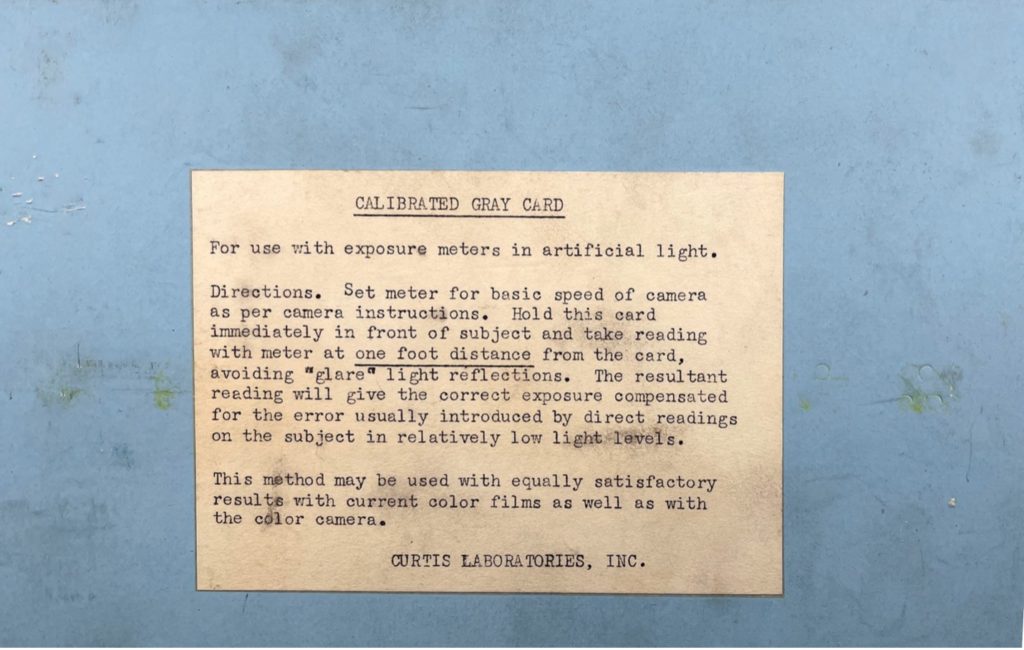

Custom calibrated gray card provided with the Curtis Color-Scout camera.

This advertisement for the Curtis Chromatone Color process shows the components needed to produce a color print from the three negatives.

Advertisement for the Curtis Chromatone Color process showing the process of stripping the emulsion of the three-color separation images from paper to create the full color print.

Jeremy Rowe

Contributing Writer

Jeremy Rowe has collected researched and written about historic photography for over 30 years. His collecting has focused on 19th and early 20th century photographs – ranging from daguerreotypes and cased images to mounted photographs, real photo postcards, and vernacular images with an emphasis on Arizona and the Southwest, Lower Manhattan, and the open-ended category of “images that strike me.”

Jeremy has curated exhibitions and served on the boards of the Daguerreian Society, National Stereoscopic Association, Daniel Nagrin Film, Theater and Dance Foundation, In Focus, and Ephemera Society of America. Jeremy is currently working with the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs to establish a National Stereoscopic Research Collection and Research Fellowship. Jeremy has written numerous publications about historic photography, including Arizona Photographers 1865 – 1920 a History and Directory, Arizona Real Photo Postcards a History and Portfolio, and Arizona Stereographs 1865- 1930. Jeremy has three degrees from Arizona State University and is an Emeritus Professor. He is currently a Senior Research Scientist at New York University and travels between New York City and Arizona.