I am thrilled to share that I collaborated with collector and Museum Trustee Tim Peterson during the past couple of years to curate one of the most comprehensive Edward S. Curtis (1868-1952) photography exhibitions to date. Years ago, my interest in Curtis was piqued when I wrote my 15-hour qualifying paper on the photographer for my master’s degree. My thesis on the early Arizona photographer and painter Kate T. Cory followed this. Interestingly, Cory had journaled an encounter with Curtis and the photographer Frederick Monsen (1865-1929) at Hopi while living and teaching there between 1905 and 1912.

In 2021, I had been eagerly anticipating the opening of our Light and Legacy exhibition at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West in October and the visitors’ reactions. I have not been disappointed with the insightful comments and critiques to date by artists, photographers, and the public as they tour the show. One of the biggest surprises people have after viewing the exhibition is the great variety of mediums in which Curtis worked.

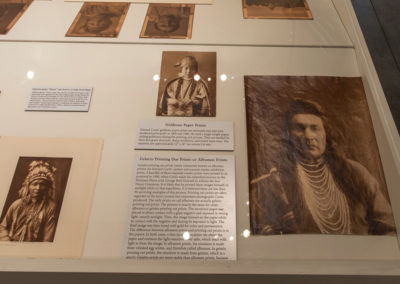

The exhibition chronicles Curtis’s The North American Indian project, one of the largest ethnological enterprises ever undertaken in American history that was concerned primarily with recording traditional customs before – as it was assumed – they would disappear. But Curtis is also renowned as a pioneer in the field of printmaking. For this exhibition, part of the focus is on Curtis’s diverse photographic mediums during his incredible 30-year career. To show the depth and breadth of Curtis’s oeuvre, Tim Peterson assembled this collection throughout many years. Some of the mediums selected for the exhibition include goldtones, platinum prints, photogravures, copperplates, cyanotypes, bromides, silver gelatins, and silver bromide border prints.

As the Curtis collection arrived at the museum in various shipments before the opening reception and preparation for the installation, I’d been eager to spend time with the material. It was a once- in-a-lifetime opportunity to handle, examine, and compare the images close-up. While planning the show, Tim, the museum’s designer Bill Dambrova, and I worked to discuss layouts. One result was Tim’s selection of eight different mediums of The Oath (1908). There are examples of this image in a goldtone, hand-colored platinum, cyanotype (reproduction), platinum print, silver bromide border print, photogravure, copperplate, and a toned silver gelatin print. Some photographs of The Oath are rare and considered masterworks.

Cyanotypes provided Curtis with initial feedback on his negatives for editing purposes while working in the field. Since color photography did not yet exist, the cyanotypes gave a tinge of color to otherwise black and white images. Curtis printed them while doing his fieldwork to see what he had achieved, or needed to complete, with his negatives. He printed nearly all his 40,000 plus negatives as cyanotypes; therefore, a large number once existed. However, these are now extremely rare since they were primarily used as field prints and discarded.

Curtis’s The North American Indian, contained 1,500 photogravures, and he made more than 98% of his prints in this medium. Throughout the exhibit, numerous photogravures are displayed next to their original copperplate. Photogravures comprise most of Curtis’s output and his extant body of work. Photoengraving was the medium that gave Curtis the subtlety he was looking for in his prints. Although expensive to make, the results were high-quality and artistic photogravures produced in quantity from 1907-1930. These sepia-toned images of Native Americans continue to speak to countless people worldwide who encounter them on postcards, book jackets, posters, galleries, and museums.

In addition to the photogravures, Curtis produced a variety of master prints. It became more and more apparent with the approximate 990 works amassed for this exhibition just how much Curtis was indeed an aesthetic and technical innovator. Today, few people have experienced prints that Curtis made for shows and sold in his studio. These are rare, representing only about 1⁄2 of 1% of his total body of work. Therefore, they comprise a tiny percentage of his total output. Nevertheless, the master prints reveal Curtis’s skills. They are considered some of his most extraordinary photographs for their beauty and artistry. For many, Curtis is most revered for his goldtone photographs printed on glass and backed with a liquid gold wash.

Curtis frequently worked in the medium of platinum prints. He produced a significant body that comprised 1⁄4 to 1⁄2 of 1% of his total production. They are rare and widely regarded as the highest form of photographic printing. The process is based on the light sensitivity of iron salts. The sensitizer is coated directly onto the paper support. The image forms within the paper fibers, resulting in a matte surface and relatively soft image. Curtis achieved the coloring of his platinum prints through a combination of watercolors, oils, and pastels. His master prints include these hand-colored images, and those such as The Oath are extremely rare. They represent a unique expression of the negative.

The terms “silver bromide” and “silver gelatin” have been used interchangeably to describe Curtis’s images. However, the term “silver bromide border print” describes a process unique to Curtis. On one sheet of silver bromide photographic paper, Curtis took his glass negative and exposed it to light, creating a contact print. However, he went one step further and made a border within a border through over-matting, thus giving the image the appearance of having an overall frame. Curtis created a small number (probably fewer than 80) as border prints. These are scarce, with generally only one or two prints per negative.

Silver gelatin prints survive for more than 1,000 negatives. However, most of these are in the archive filed initially with the Copyright Office. In addition, a small body of Curtis’s silver gelatin prints was made for exhibition and sale on papers varied in texture, weight, and finish. His toned silver gelatin prints are typically warmer than his platinum prints and are relatively rare.

Curtis’s printing out process is infrequent, and the late Christopher Cardozo reported that maybe only 30 or so of these types of images have survived. According to Curtis’s great-grandson, John Graybill, Curtis did this process briefly, probably between 1898-1899 and possibly until 1900. Curtis shot the image using a glass plate, then processed the plate in the tent and made a printing-out paper contact print in the field.

Curtis held numerous photo exhibitions, wrote magazine articles and books, created a lecture series, and combined his lantern slides with a live orchestra to create the “Picture Opera Musicale.” He also produced a feature-length narrative film, In the Land of the Head Hunters (1914). He made thousands of audio recordings of songs, ceremonies, and stories. Curtis helped found the Indian Welfare League (1923) that sought to advance understanding and appreciation for Native Americans.

For some years, I have seen how Curtis inspires and transforms lives in various ways. In 2012, I taught a course on Africa, Oceania, and Native American art at the University of Arizona, where I experienced this firsthand. After showing In the Land of the Head Hunters and looking at Curtis’s photographs, one student wrote to me: “I listened to one of the songs before I left home … very moving … I felt vibrationally – what the singer was projecting. Vern, the cat I am taking care of, came by the computer to listen. He stayed until it was over. I think he felt the spirit too. Thanks a lot. I am glad I heard the song before I started the day. I did not know who Curtis was, but I was captivated by the young girl’s photo. I have seen it lots of times.”

To listen to an excerpt of Curtis’s wax cylinder recording of Skalan Hola (Song Sweet), a love song performed by Stahmai (John Wesley) on May 20, 1913, click here. Stahmai was a member of the Haida people of Skidegate on Haida Gwaii (formerly the Queen Charlotte Islands), British Columbia. Courtesy of Indian University’s Archives of Traditional Music.

Visit Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West Light and Legacy page here.

Feature Image Photo Credit:

Curtis’s copperplates and photogravures printed for The North American Indian. On loan courtesy of the Tim Peterson Family Collection.

Exhibition photo courtesy of Loren Anderson Photography.

Dr. Tricia Loscher

Contributing Writer

Dr. Tricia Loscher is an Arizona native and has a background in both non-profits and academia. She serves as the Assistant Museum Director – Collections, Exhibitions, and Research at Western Spirit: Scottsdale’s Museum of the West, where she leads the storytelling and presentation of all exhibitions at the museum, whether curated by her and the museum team or co-curated with guest curators. She has curated exhibitions ranging from the Taos Society of Artists to the Cowboy Artists of America. More recently, she co-curated the world’s most comprehensive retrospective exhibition to date showcasing Maynard Dixon’s lifework and artistic career, as well as one of the most comprehensive exhibitions ever mounted on Edward S. Curtis. Before Western Spirit, she was the curator and program director for the Heard Museum North in Scottsdale. She curated Navajo folk art and retrospectives on the artists Allan Houser and T.C. Cannon. Dr. Loscher has taught contemporary art and non-western art history courses at universities in the southwest and overseas and has published articles on art and artists of the American West, including Kate T. Cory, Artist in Hopiland and a book entitled Old Traditions in New Pots: Silver Seed Pots from the Norman L. Sandfield Collection. She holds a Ph.D. from the University of Arizona and an M.A. and B.A. from Arizona State University in art history and education, with minors in Latin American art, anthropology, and museum studies.