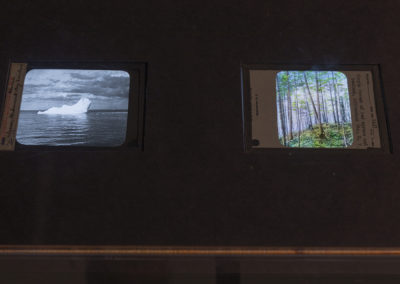

The title taken from a line in Mary Oliver’s poem, “Among the Trees,” the exhibition, trees stir in their leaves, is an immersive art and science installation resulting from a two-year collaboration with the University of Arizona’s Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research (LTRR). Held at the Center for Creative Photography until July 23, 2022, the installation surveys trees within the history of photography— from modernist experiments in formalism and symbolism, to contemporary image-making, which explores the medium’s ability to address our most pressing challenges today. The cross- disciplinary show features photographs that span the late nineteenth century to the present, weaving between hand-painted glass plates, digitized Kodachrome slides, gelatin silver and inkjet prints, and photomicrographs.

Photography’s relationship to dendrochronology (the study of annual rings in trees) stretches back more than 100 years to the discipline’s origins and founder, Andrew Ellicott Douglass, a scientific polymath who moved first to Flagstaff and then to Tucson just after the turn of the 20th century. Douglass was, by all accounts, a tech enthusiast. He documented and demonstrated his scientific discoveries using the latest in visual technologies, as well as collected photographs by colleagues from around the globe. Douglass also invented a handful of new optical instruments, the most intricate of which was his “cycloscope.” An analog computation device, the cycloscope assembles light, lenses, mirrors, and gears to determine solar cycles through the study of tree-ring data. Dormant for nearly 70 years, the 1936 version of Douglass’ “Merriam Cycloscope,” the only one of its kind, is exhibited to the public for the first time in CCP’s new Alice Chaiten Baker Interdisciplinary Gallery. Due to spatial constraints, we were able to display only 25 feet of what is in fact a 40-feet- long instrument. Truly, you must see this cycloscope to believe it.

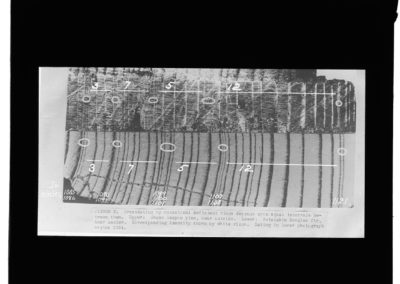

Photography is interspersed throughout tree-ring studies, arguably forming an integral part of this modern discipline. For instance, photographs have been used as measuring tools to compare ring growth between trees at different locations (called “crossdating”), and photographs serve as methods in studying the microscopic and macroscopic details of trees. Scientists deploy photographs to substantiate their data to the public, sometimes with the hope of eliciting an emotional response to the information they are sharing. Historical photographs offer insight to forest composition and land use, and dendrochonologists today use rephotographic techniques to tell the story of a tree site over time. During our massive opportunity to deep dive into LTRR’s collection of tree images, we also discovered the unexpected: historical photographs of earthquake damage, colonization of the west, deforestation, mountain glaciers, and archaeological excavations. As well, a 1960s golf outing too…go figure! It is an image collection ripe for continued research.

And, it is a collection that made for an easy symbiosis with CCP’s collection, itself filled with photograph upon photograph (upon photograph!) of trees. Trees have been an enduring source of inspiration for artists, and the photographs chosen to be exhibited from CCP’s collection run along two parallel lines that inform each other: one being artists for whom trees cameo only occasionally in their work, and the other of artists intensely preoccupied by trees. The Aaron Siskind archive alone comprises a mountain of work prints he made of trees over multiple decades, from Bloomington and Martha’s Vineyard to Corfu and Oaxaca, from apple trees and birch trees to olive trees and oak trees. Since 1991, Barbara Bosworth has photographed the United States’ “champion trees,” the largest known trees of each species based on reports from American Forests, while Kozo Miyoshi has imaged Japan’s cherry blossom front (“Sakura front”) during the springtime for over two decades. I have spent a fair amount of time wondering what each learned—what new meaning they found—from such a deep engagement with trees.

In part inspired by Valerie Trouet’s Tree Story: The History of the World Written in Rings, timely released in 2020, trees stir in their leaves is an ode to the stories found in trees. Stories about ecological change, droughts, floods, forest fires, pollution, earthquakes, solar flares, and the rise and fall of civilizations. The ancient Bristlecone pines, the oldest known tree species in the world, have been witness to natural and human histories for thousands of years. In the exhibition is a wood segment at the pith from one such pine (“Prometheus”), over 4,000 years in age when accidentally cut in the 1960s, with the most remarkably slender rings. There are also several images, taken as long ago as c. 1920 and as recent as 2021, of the Methuselah in the White Mountains, the most senior of Bristlecone pines as the oldest tree to have ever been dated. The Bristlecone pines are brimming with our histories, helping scientists in their identification of global famine (2036 B.C.) and volcanic eruptions (43 B.C.) to global warming (c.1850) and atomic testing (1951-present).

Artists, by the same token, build stories about culture, politics, memory, identity, and community through trees. Ansel Adams’ large-scale and unglazed Redwoods, Bull Creek Flat, California (c. 1960) points to the feeling—the grandeur even—of nature. By this time, Adams was of course deep into his efforts for environmental conservation, working across multiple political and cultural registers in hopes of affecting broader environmental concern and policy change. Rosalind Solomon’s sobering photograph April Apple Orchard Two Years after Chernobyl, Eastern Poland (1988) is a single mangled tree that becomes evidence of the 1986 nuclear power accident, simultaneously human and natural catastrophes. In the currents of international news about Russia’s cruel invasion of Ukraine, this historical tree also raises the alarm for our possible futures. Trees alternate between beacon, refuge, caution, landmark in a 2017 photograph from Dawoud Bey’s Night Coming Tenderly, Black, a series of landscapes atop of which the histories of the Underground Railroad and self-liberating people took place. I am now convinced that trees can hold the visible and otherwise invisible stories that shape our lives.

trees stir in their leaves is a purposeful layering of the LTRR and CCP’s image collections. Our intention with this unconventional approach to installation design was to fuse the human stories and the stories scientists tell through trees, and it lead to new thinking about openness, interconnections, and creativity in experiences with photographs. In partnership with the University of Arizona’s Campus Arboretum, we took the experience of the project further by developing a map and self-guided tour of trees stretching along paths between the Center and the Tree-Ring Building. It was a chance to connect our photographic collections to the life happening outside our institution—as all photographs are.

Feature Image: Pinus ponderosa (ponderosa pine), Photograph taken by P.N. Knorr, Santa Rita Mountains, Arizona, 1978, digitized from Kodachrome slide, © The Laboratory of Tree-Ring Research, University of Arizona

Meg Jackson Fox, Ph.D.

Contributing Writer

Dr. Meg Jackson Fox is Curator, Interdisciplinary and Community Practices for the Center for Creative Photography, University of Arizona. She has an M.A. in Modern History from the University of Tennessee; an M.A. in Art and Museum Studies from Georgetown University, jointly convened with Sotheby’s Institute of Art-London; and a Ph.D in Art History-Contemporary Art & Theory from the University of Arizona. Jackson Fox draws from a research base that uniquely sweeps from western Europe through eastern Europe to North America. A twelve-year background teaching in universities and cultural institutions, Jackson Fox maintains a rigorous program of speaking and publishing locally, nationally, and internationally, and is currently working on her first book manuscript, Movement(s): Essays on Art, Politics, and Running.

Contact Meg