Feature Image: Cover of Southern Arizona Mining by Jeremy Rowe (Arcadia Publishing 2023)

As well as a faithful blog contributor, a curator, researcher, historian, and collector of historic photographs, Jeremy Rowe is also a published author. He was kind enough to answer some of our questions about his experience getting published. At the end of the Q&A, you’ll also find an excerpt from his recent book Southern Arizona Mining.

AZPA: What made you decide to write this book?

JR: I try to share images from my collection with as correct a source and attribution as possible. I had previously worked with Arcadia and found it a cost-effective way to share images with my descriptions, and to include a bit of history about photographic processes to educate readers. The distribution network Arcadia has built is a great way to get many copies into circulation in ways that have been difficult for me when working with small publishers on other more substantial books.

I have many clusters of images in my collection. As I was working with my collections, historic Arizona mining bubbled up as a potential topic. I was particularly interested in showing images of now abandoned areas that only exist today in historic photographs and postcards. Initially, I was planning to focus on historic Arizona mining up to circa 1920, but there were so many images that I broke it into several sections. The first is Southern Arizona, with plans to follow up with similar books that focus on mining communities in central and northern Arizona.

AZPA: Did you contact Arcadia to get it published?

JR: I published Early Maricopa County 1871-1920 with Arcadia a few years ago. It was initially a way to provide a catalog of the images I used to display at the Talking Stick Resort. After a meeting with the architect and project team, the concept of using historic photographs in the hotel decor was established. Using historic photographs of the region and people, copies were made and framed. An exhibition of the images selected was installed in the convention center and a catalog with interpretive descriptions was planned. Just before opening, the casino/hotel changed administration and project priorities shifted. As a result, the catalog was not produced. To document the exhibition images and provide access to a broader audience, I expanded the content. Arcadia Press was interested in the project, eventually publishing the Early Maricopa County 1871-1920 book in 2011. The title sold well enough that Arcadia periodically approached me for another. Last Spring, I had a window. When they reached out again, I negotiated the new Southern Arizona Mining.

AZPA: How was the publishing process for you as author and photographer?

JR: Since I owned the images, it eliminated issues and costs associated with purchasing reproduction rights. Arcadia has a tight format that I’d worked with before and was able to negotiate a few changes that I was able to carry forward for the current book project. Arcadia has a process of hand-offs and progressive interaction providing guidance and feedback and permitting some opportunities for negotiation. The Arcadia template is structured in terms of word count and captions. The format provides an interesting challenge to balance and spread content between the short chapter introductions and the image captions. Also, Arcadia has a reputation for varying quality of images used in some of their books. I had control over the scanning, and despite a couple of images that turned out not quite as I hoped, most of the reproductions worked as well as possible within their publication model.

AZPA: How many images did you start with before choosing the final 190? How hard was that? Did anyone help you with that?

JR: I have many hundreds of historic images of mining, miners and mining communities in Arizona from the mid-1860s into the 1940s. It’s hard to note the initial number of images. The project started with a few clusters of images, some from well-documented areas like Clifton, Morenci and Bisbee, and others that only exist in the photos and postcards like Johnson and Copper Creek. I also wanted to share as many images as possible that had not been previously published.

I had full editorial control over everything but the cover, which I provided several potential images and negotiated with Arcadia. They have guidelines in terms of placement to title and text and spine wrap which restricts the use of some potentially wonderful images. Happily, I was able to use one of the images I wanted.

This project was different than one many AZPA members would undertake with their own images. It involved selection of historic images produced by others, as opposed to my own photographs. I’ve worked on several “then-and-now” projects where I helped plan many of the comparison images and selected contemporary “now” photographs to pair with historic “then” images.

AZPA: Any advice for other photographers thinking about publishing their own book?

JR: In terms of advice, I’d say try to keep realistic expectations about the process and interacting with the potential publishers. Once you have a contract, build a relationship with the editors and publications staff to help you get better feedback and identify opportunities for negotiating. Also, keep realistic expectations for distribution and the difficulty of small publishers penetrating many markets like museums and libraries who tend to buy only from a few large distributors.

Excerpt from Southern Arizona Mining by Jeremy Rowe

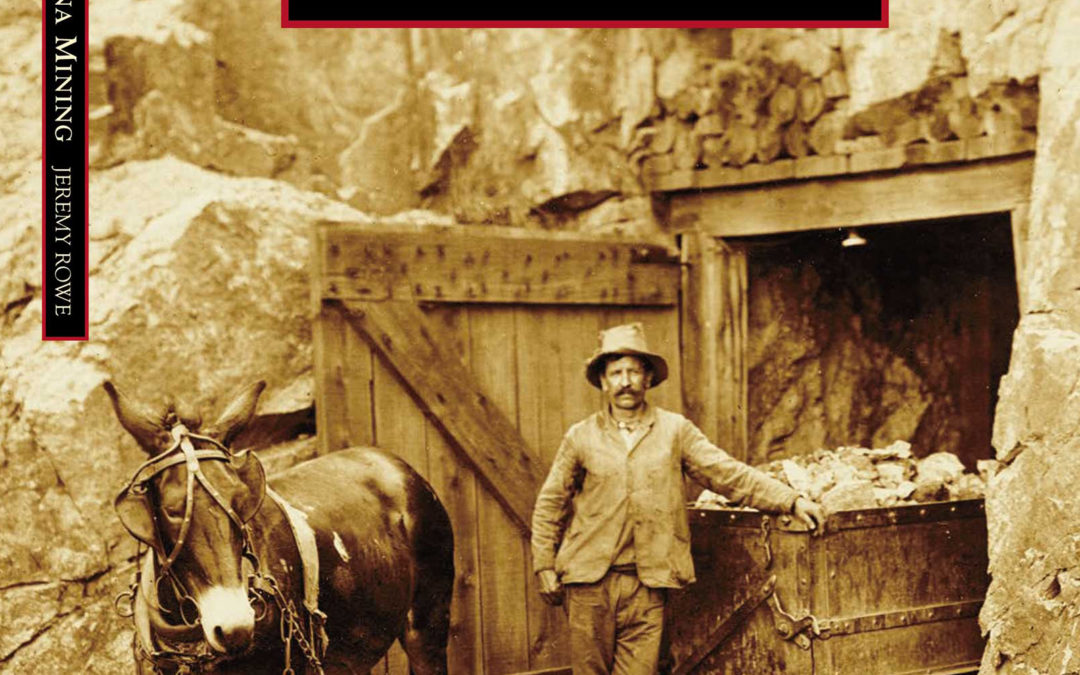

Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Mallonee, c. 1917. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

In 1909, F.H. Mitchell, the general manager of the Johnson Development Company, brought in new machinery to sink the shaft to 200 feet. This view shows the vertical headframe and hoist building that housed the 40-horsepower gasoline engine and air compressor to power air drills behind the tailings of the Johnson Developing Company mine in the Southeastern of Arizona.

The development and popularity of the real photo postcard in early 20th century aligns with the boom, and occasionally the bust of many of the smaller mining communities in southern Arizona. The stories of the mining operations and towns that grew around them were often documented in real photographic postcards. One such town that exists today almost solely through a collection of real photographic postcard images that has been assembled by the author is Johnson, Arizona.

Mining operations in the southeastern corner of Arizona began on the east side of the Little Dragoon Mountains in Cochise County in about 1881, when the Peabody, Republic, and Mammoth mining claims led to the establishment of Russellville. The copper camp of Johnson initially grew slowly nearby, eventually justifying the establishment of a post office in 1900. Growth of the little town of Johnson quickly surpassed Russellville, and quickly reached a population of 317 in 1902.

The Johnson Copper Development Company was soon capitalized at $300,000, and Colonel Greene purchased claims and established the Greene Consolidated Copper Company. Both mines were soon shipping a carload of high-grade ore to a smelter in El Paso, Texas by rail every day. The Bisbee Daily Review noted, “Johnson will take on a new life and undoubtedly add another producing camp to Arizona’s list of big producers of copper.”

In May 1909, the Black Prince group struck a body of sulfide ore that yielded 25–35 percent copper at a depth of 430 feet. The Centurion mine found ore at a depth of 160 feet that yielded 25 percent copper.

By 1910, the Peacock Copper Mining Company had erected a hoist and had two carloads of ore ready to ship. The Arizona United Mines Company built and ran its own 125-ton smelter, and it, the Centurion, and Black Prince were all regularly shipping ore for processing.

The year 1916 saw the largest output of the mines at Johnson. The Cobriza Company was shipping four cars of ore a day. The Arizona Michigan mine shipped one or two cars a day to the smelter at Douglas, and the Peabody Mine was shipping about three carloads of ore a week.

Active groups at Johnson at this time included the Black Prince Mine, Peacock Mine, Arizona Copper Shipping Company, Arizona and Michigan Company, United Mines Company, Keystone Copper Company, St. George Mining Company, Cochise Development Company, Johnson Copper Development Company, Sims Mountain Copper Company, Centurion Company, and Empire Copper Company.

An itinerant young photographer, Dale T. Malonee traveled throughout Arizona from about 1916 – 1920. Malonee visited Johnson to document the productive mines and growing community in 1917. He and several other photographers produced a series of real photo postcards of the mines and growing town of Johnson during this boom.

The Johnson District was able to avoid the labor unrest that hit Bisbee, Clifton, and other mining communities soon after America entered World War I on April 6, 1917.

By 1918, mining production around Johnson continued to be strong, with Arizona United Mines typically shipping four carloads of ore a day from Johnson by rail to the smelter at El Paso.

By 1925, the population of the town of Johnson had a grown to about 1,000, but the dropping price for copper that continued in the economic turmoil that began after World War I led to cutbacks at the mines, and triggered emigration from Johnson to other more successful mining communities. The post office at Johnson finally closed in 1929, and Johnson was well on the path to becoming a ghost town. Years later, there was a brief resurgence in the region, when some copper, zinc, and silver mining resumed after World War II.

Today, little is left of Johnson, Arizona other than a small ephemeral group of real photographic postcards that were made by itinerant Dale T. Malonee and anonymous photographers.

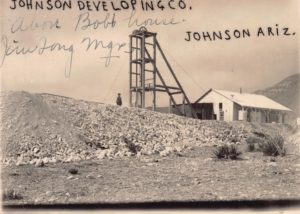

Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

This booster ad was run on May 14, 1916, by J.T. Tong in the Bisbee Daily Review. The ad promoted the camp and its productivity stock offerings for his company in Johnson, Arizona.

Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

The hoist, engine house, and operation at the Black Prince Mining Company were in the foothills of the Dragoon Mountains about a mile north of Johnson. In 1909, the 160-foot- deep Centurion Shaft at the Black Prince struck a rich, six-foot thick, 25–35 percent copper ore vein at 430 feet that produced ore at 25 percent or better copper. But by 1915, only 10 men were working at the mine.

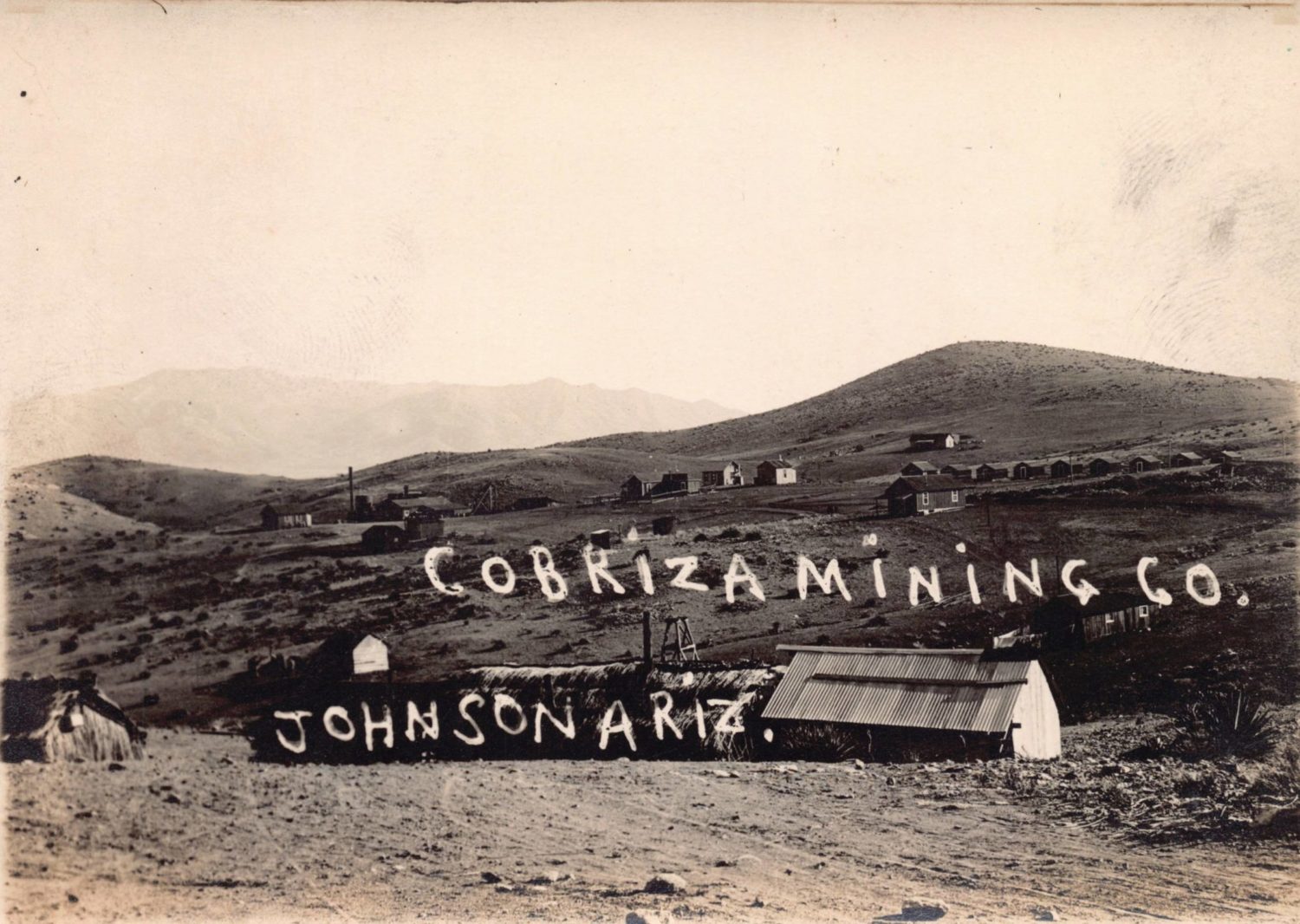

Silver print, photographer unknown, c. 1917. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

The Republic Mine at Johnson was operated by the Cobriza Mining Company. Note the large fresh slag heap of material removed from the mine in the foreground.

Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Mallonee, c. 1917. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

The Cobriza Mining Company shipped up to 5,500 pounds of ore a month from its operations at the Republic and Mammoth Mines in the Johnson District. In 1916, the company grew its operation by purchasing the 60-acre smelting plant and silver and lead slag dump at Benson, Arizona.

Cropped real-photo postcard by Dale T. Mallonee, c. 1917. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

The Arizona United Mines Company built a 125-ton smelting plant in 1909 to expand capacity as mining in Johnson output grew. The smelter closed in 1916 when the Southern Pacific Railway attempted to raise shipping costs for ore from Johnson. After transportation rates were stabilized by the Arizona Corporation Commission, the smelter resumed operation.

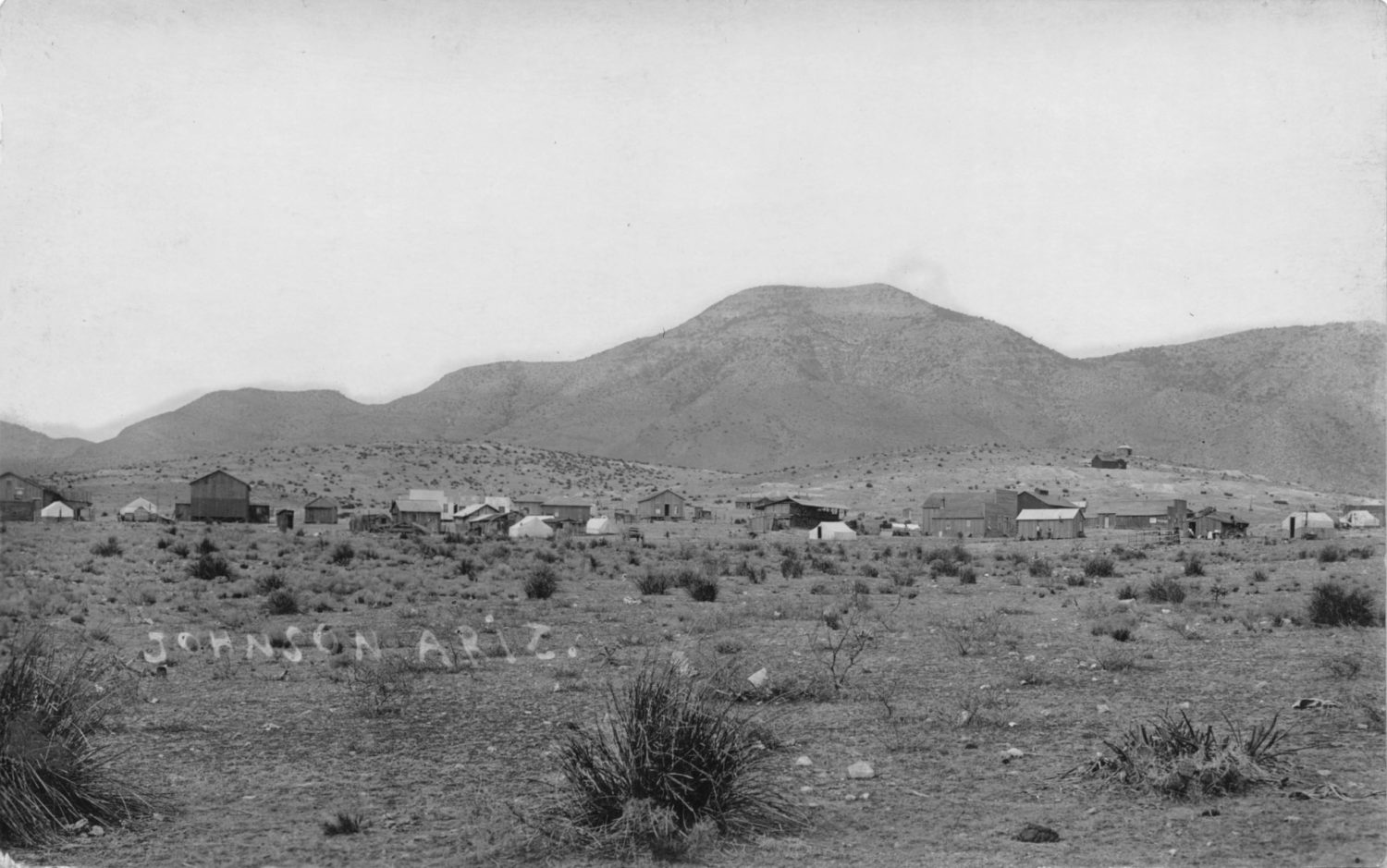

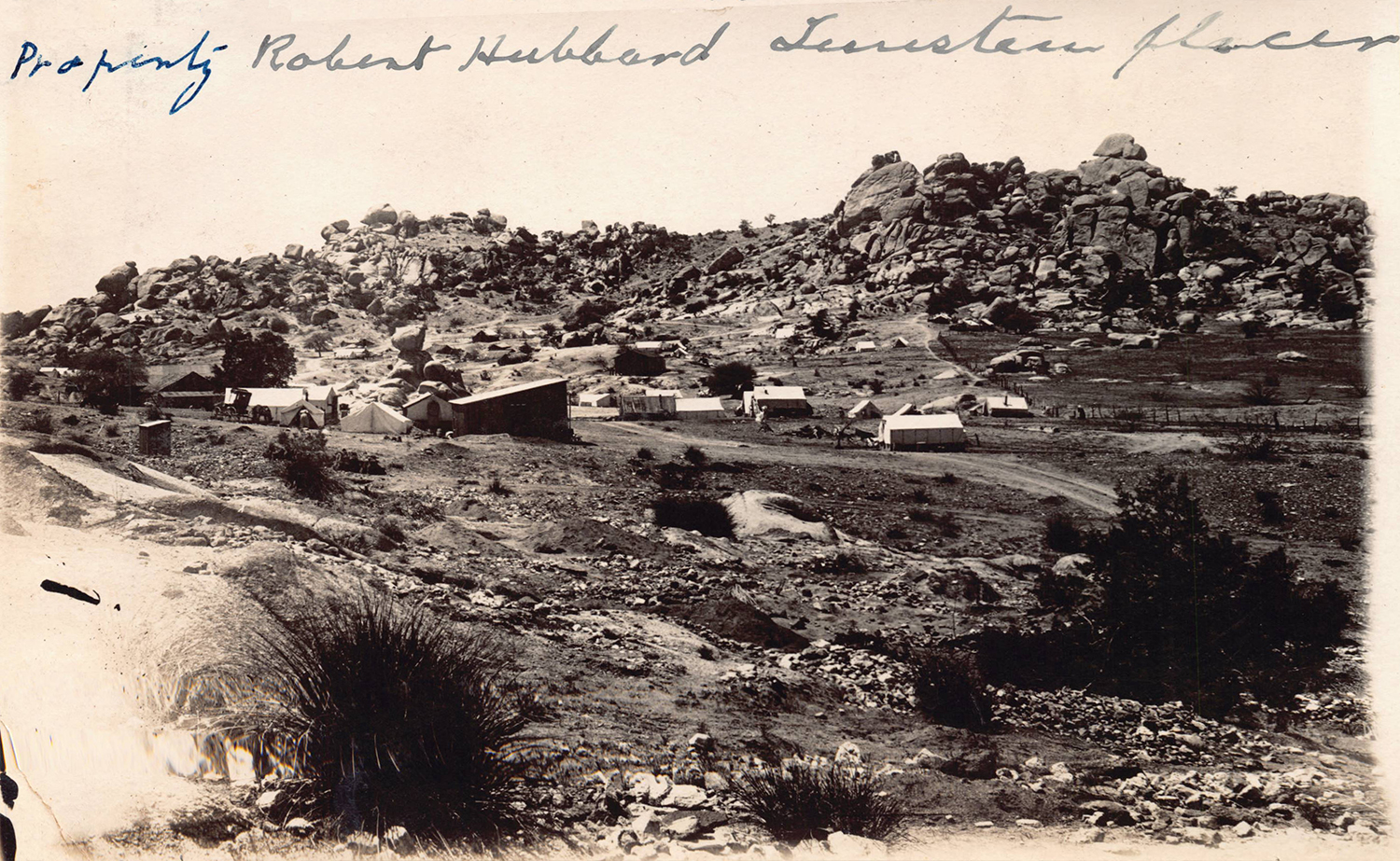

Real-photo postcard, photographer unknown, c. 1915. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

In 1912, increasing prices for copper drove even greater mining activity in the Johnson District. The town had grown to three miles long and was a mile wide from east to west on the eastern side of the Dragoon Mountains. This overview shows a mix of rapidly constructed temporary wooden and canvas residences that interspersed the more permanent wooden structures that made up the town of Johnson during this era.

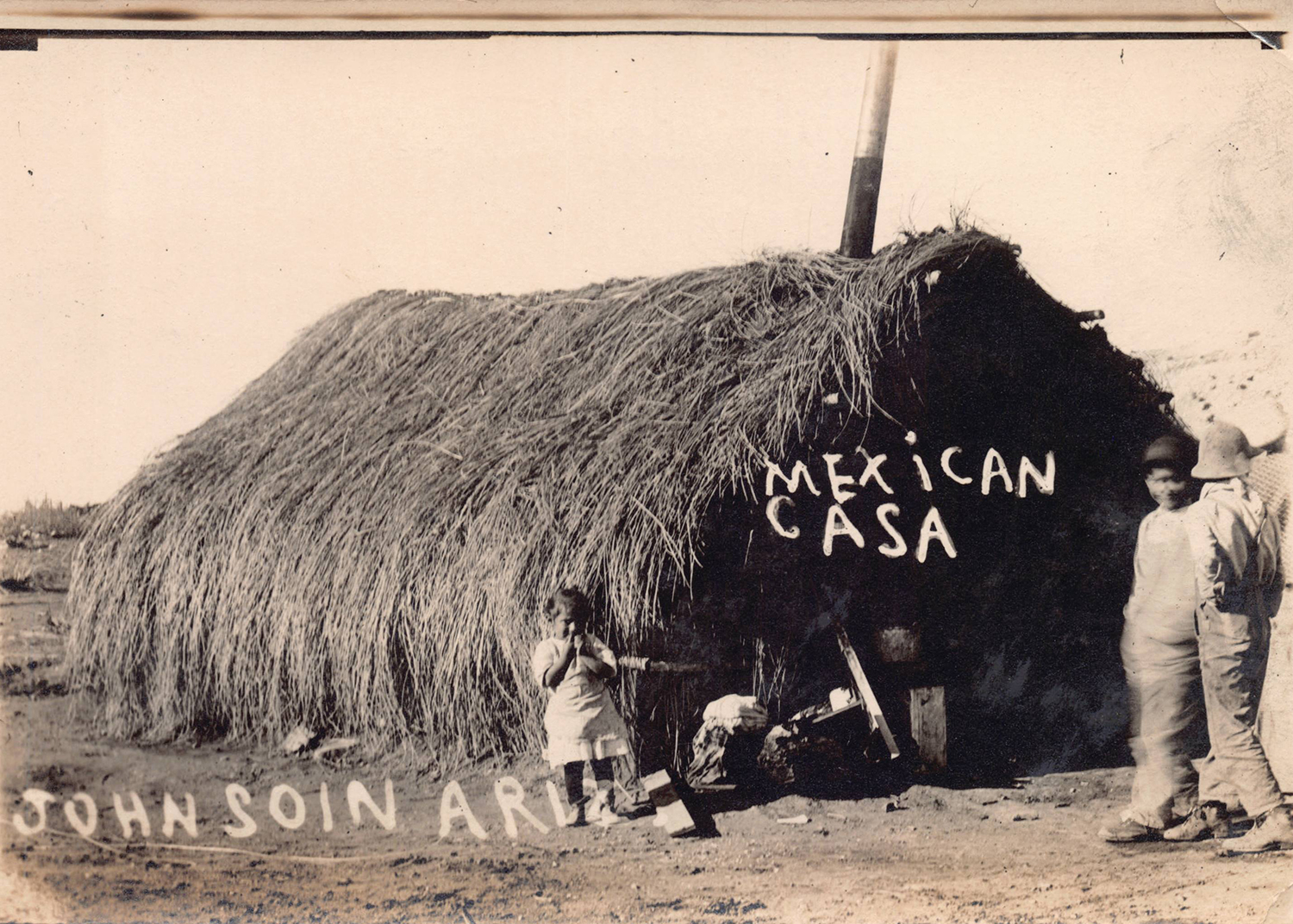

Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

Housing in the rapidly growing mining communities of southern Arizona needed to be built quickly and varied dramatically in scope and sophistication. This image shows a thatched hut that was a far cry from even the typical simple canvas and pallet temporary housing for miners during this era, let alone the more formal wooden structures that followed as the towns adjacent to the mines grew.

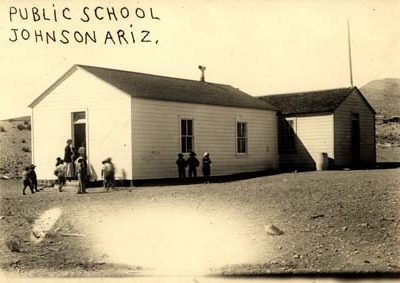

Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

As families joined the communities, amenities like schools and churches were built. This image shows the new one-room schoolhouse that was built at Johnson, led by female principal Mollie Brown who is posed in the doorway.

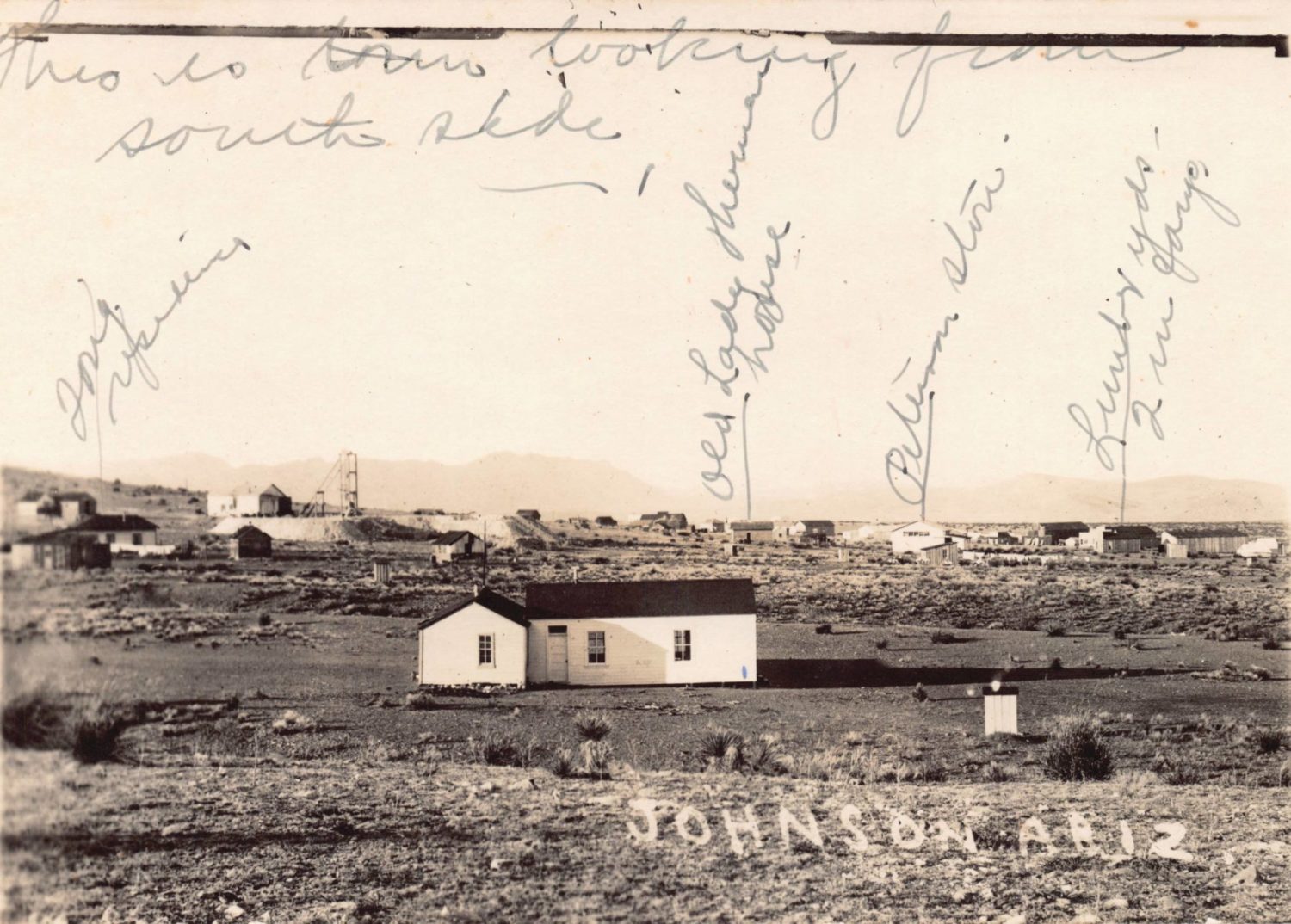

Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

This view is looking north across the Johnson townsite. The period manuscript identifications include J.T. Tong’s home, Old Lady O’Hara’s house, the Picture Store, and the lumberyard. Note the headframe of the Johnson Development Company behind the town on the left.

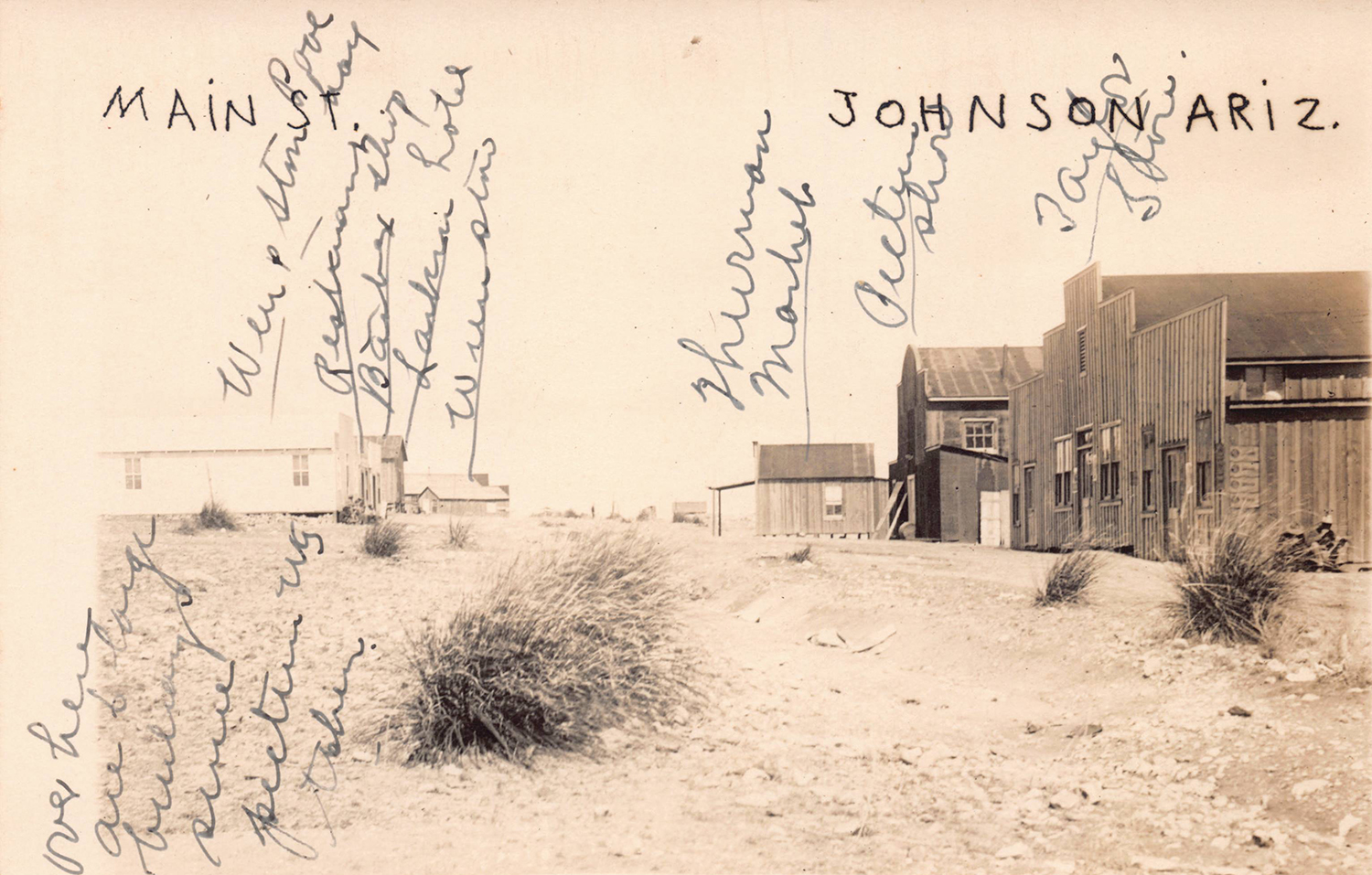

Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

This view looks down the Main Street of Johnson, Arizona from the storage buildings at the edge of town. Manuscript locations noted include Wen & Stein pool hall (one of three in Johnson), a restaurant (Perry & Sons), a barbershop (A.L. Martin), T.B. Larkin’s rooming house, A.H. Wein’s general store, Albert Thurman’s meat market, William Seliger’s Picture Show, and B.A. Taylor and L.W. Rader’s general store.

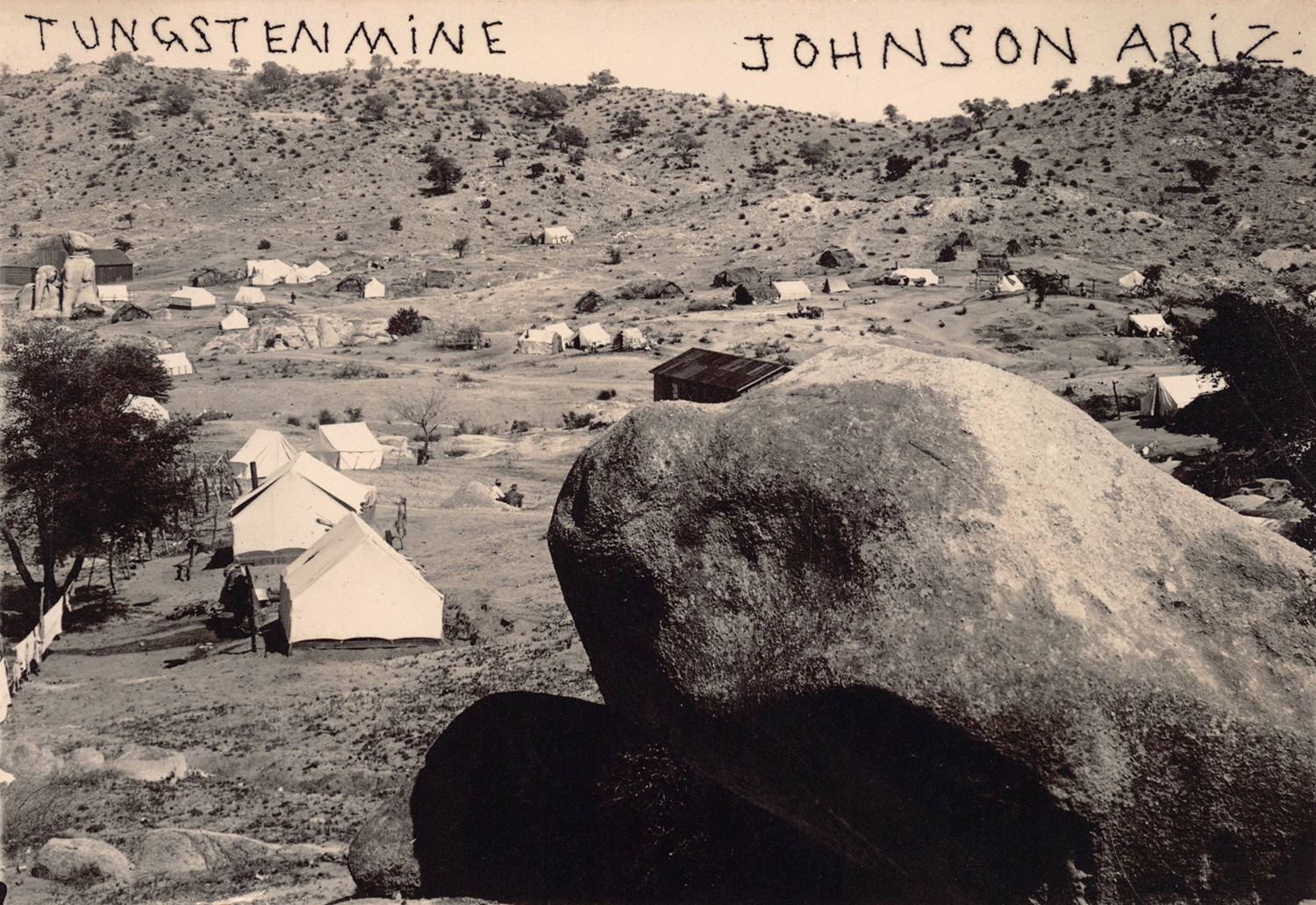

Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

Johnson had some of the richest and purest deposits in the United States at the beginning of the tungsten boom. An assay of one deposit was valued at $19,000 per ton of ore.

Real-photo postcard by Dale T. Malonee, c. 1917. Collection of the author © vintagephoto.com.

This is probably a view of the Primos Chemical Company operation about five miles from Johnson. The boom eventually led to surpluses of the precious metal and dropping prices.

Jeremy Rowe

Contributing Writer

Jeremy Rowe has collected researched and written about historic photography for over 30 years. His collecting has focused on 19th and early 20th century photographs – ranging from daguerreotypes and cased images to mounted photographs, real photo postcards, and vernacular images with an emphasis on Arizona and the Southwest, Lower Manhattan, and the open-ended category of “images that strike me.”

Jeremy has curated exhibitions and served on the boards of the Daguerreian Society, National Stereoscopic Association, Daniel Nagrin Film, Theater and Dance Foundation, In Focus, and Ephemera Society of America. Jeremy is currently working with the Library of Congress Prints and Photographs to establish a National Stereoscopic Research Collection and Research Fellowship.

Jeremy has written numerous publications about historic photography, including Arizona Photographers 1865 – 1920 a History and Directory, Arizona Real Photo Postcards a History and Portfolio, and Arizona Stereographs 1865- 1930.

Jeremy has three degrees from Arizona State University and is an Emeritus Professor. He is currently a Senior Research Scientist at New York University and travels between New York City and Arizona.